Archive

- January 2026

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- January 2023

- September 2022

- August 2022

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

Zakopane

After leaving Krakow in early November of 2022, I took a bus about an hour south, to the town of Zakopane, in the Tatras Mountains on the southern border of Poland. This is just about the only place in Poland which has mountains, the rest of the country being essentially pancake-shaped. Dismounting the bus, I walked about a mile up a long road lined with all sorts of shops and cafes, crowded with people who had come up to the hills to hike. In winter, Zakopane is a ski town, and already it felt like one. I stayed in the smallest Airbnb I’d seen – a room built as an annex on the side of a stone house, which, including the bathroom, was probably about ten feet long and five feet wide. But I actually found this incredibly cozy, especially since it made the place easier to heat, since it was already getting quite cold.

The next day I went for a walk. The first thing I noticed about Zakopane is the peculiar local architecture – a style which is now known as Zakopane style, pioneered by architect Stanislaw Witkiewicz, who inspired the region to shift away from Swiss- and Austrian-style chalets and toward a style of architecture inspired by the more local traditions of the Goral people and the Carpathian Mountains, of which the Tatras are an extension. As a result, Zakopane today is a wonderful collection of tiered-roofed wooden houses that don’t quite look like anywhere else.

As I headed uphill into the wooded foothills of the mountains, and saw the rotting bracken and the dripping moss, the dark firs spattered here and there with bursts of rain, breathing out fog, and everywhere the drip of water on every surface, I realized that if I were dropped in this place with no context for where I was, I would absolutely believe I was back in Washington. It had exactly the same character and climate, and immediately I began to feel a hospitable comfort, a kindred warmth brought on by the gloom and the rain.

As I proceeded, I passed the old habitations of people who once lived in the forested hills, before it became a national park. Amid the dark firs were blanched larches, gold fading into the fog. The trail quickly climbed into the clouds, up a long stair of stone that made me feel like a hobbit on the way to Mordor. Then as I clambered up a slope, there was a sudden break in the fog, and sunlight revealed an immense and craggy escarpment on the other side of the defile.

From there, it was only a short walk through the woods until I suddenly popped above the clouds and into winter. I rounded a corner and without warning was in a world of white mountains and snow-capped Christmas trees, as far as the eye could see. The trail became a gentle stroll through this garden of snow, until I came to a high valley dotted with tiny cabins, ringed with an amphitheater of proud peaks. There I rested and stared, until I finally became too cold and retraced my steps to the town below.

The next day I had thought to get a local train or bus into northern Slovakia, assuming that would be feasible because the distances involved were small – but I soon discovered the transit system was not oriented toward getting people into the middle of the Slovakian hills. After a tiresome morning lugging my gear from one bus station to another and back again, I finally caved and decided to return to Krakow for the night, and catch the bus to Budapest the next day. But I’m glad I went back to Krakow after all, because that night I took a stroll around the great market square in the darkness, and found it transformed into a study in contrast, inky sky above, warm lights below, and everywhere the gentle babble of relaxed voices from the cafes, like ripples on the strand.

Music in December 2023

The final monthly playlist of 2023 is bookended by Joe Hisaishi’s score for what seems like Hayao Miyazaki’s swan song, The Boy and the Heron. This score repeats a few themes at critical junctures in the story, when everything goes silent, and suddenly the first piano chord announces itself like the Last Dawn, and all the shadows of every cloud and tree dance over the green.

In another original score to an anime film, RADWIMPS once again transform themselves from a rock band into a gentle and stripped down musical chimera, and also collaborate with yet another singer, to great effect. Suzume is all about the strange otherworld spaces that lie just beneath our own world, and its score perfectly evokes that sense of vast, mystical hollow space, with all its strange beauty.

The inclusion of the next few songs are all symptoms of me being chronically online: Amour plastique featured in a series of memes about Napoleon coincidental with the release of the film (I love it when the humor of the youth latches onto something historical); Duvet popped up in a set of even more obscure memes that I’m not even sure I fully understand; Crystal Dolphin was one of the many contemporary remixes based off ‘80s city pop to feature in a specific genre of youtube film edit that I am obsessed with; and Necromantic is pure meme fuel, where the meme is essentially just about how darn catchy it is. But that’s the thing – all of these are genuinely good.

Strange Conversations takes its time to work up to a sort of reverential musical alchemy that successfully evokes the feeling of sacred space. And No Surprises has a similar sort of powerful rip tide current, driving inevitably through a beautiful melancholy. Whereas Wake Up injects its own melancholy into the body of an uplifting chorus – yet still manages to come out strangely sad. I remember back when I first heard this a decade ago, I was fully obsessed with it.

I had never really spent a lot of time listening to Springsteen, but after hearing an excellent podcast about him, I’ve come round. Dancing In the Dark feels particularly appealing to me, because it’s a musical expression of frustration at one’s own inability to get anything done – which is something I feel almost every hour.

New Order’s Ceremony seems to creepy and mumble its way shyly by, to the degree that it almost doesn’t fully arrive – you might miss it as it goes past, but that would be your loss.

I listened to Michael W. Smith’s classical album Freedom a great deal in the first decade of our century, and now I’ve returned to it after a long break, to find it as great as I remembered. There’s a wonderful musical clarity and urgency to its melodies, like rivulets of cold water over rocks, and it does a far better job of being ‘epic’ than most modern orchestral music that goes out of its way to try. It is at turns sweeping and domestic, vast and close.

I have a whole playlist of choral carols I like to hear at Christmas. There’s nothing quite like the dignity of an English choir, proceeding with a steady old hymn, and playing on both the beauty of the cold snowy night and my own incredibly sharp longing for England.

Then, more ASIAN KUNG-FU GENERATION, the old reliable rockstars of my year, bringing the warmth of the summer sun to darkest winter. And after, more Japanese film scores: the wonderfully fluid and rippling work of Umitaro Abe, and more of the brilliance of Hisaishi, in all his imaginative sonic diversity. There’s nothing more peaceful and calmly beautiful than Summer.

A rougher note is struck by Great Grandpa’s Rosalie, a raw nerve exposed to the cold grey rain I know so well. This is masterfully done.

I got into Kenshi Yonezu and Kensuke Ushio’s work for the show Chainsaw Man, which has both the aggressive energy its title implies, but also a muted quality – which extends to Ushio’s other work as well, which is always beautifully deflated.

Finally, I end the year with The Boy and the Heron once again, which is itself the perfect sendoff. The entire film, right down to the score, is about reckoning with a life already lived, and the impossibility of legacy – or at least of controlling it. There is no perfect way to say farewell, to set all things in order as we planned – as I learn again and again, day after day. But in that great collapse, there is a kind of ultimate release, like splitting an atom, when the veil of reality is rent, and the possibility of eternity shines through.

Music in November 2023

The most recent album from The Mountain Goats, Jenny From Thebes, has a fresh, rain-washed feel to it. Darnielle’s work is often lo-fi, but this is crisp and clear, shining like a freshly-washed car, and like all his work it’s an exquisite entanglement of melancholy and optimism. This sort of music is perhaps better calibrated to the actuality of life than any other – but there’s also a sort of inexplicable mystery, because I can’t explain quite why it’s so profound.

Jo Yeong-wook’s score for the 2016 film The Handmaiden is a quivering tapestry of trepidation and anticipation, which weaves itself into ever greater splendor, like a silkworm spinning its thread. Meanwhile, Martin Dirkov’s score to last year’s Holy Spider is oppressive and ominous, a soundtrack that wears a hard grimace.

Then we have two great songs from the ‘80s – Randy Crawford’s One Day I’ll Fly Away and Vanessa Paradis’s Joe le taxi. Both create a sort of warm and dreamy cloud upon which carries the listener away.

I was really into Mae back in high school, and I think their album Singularity still holds up really well, especially its pitched-up synth lines.

Rainbow after tears is exactly what its title suggests. Just as the original rainbow of the Noetic flood, Saho Terao’s song has the feeling of life springing back into bloom, shaking off death’s torpor and greeting a surprising new tomorrow.

Next are three more ‘80s songs, all with the feeling of being simultaneously within and without – under and endless low ceiling of grey clouds, off which the music echoes endlessly. This is exactly what I love about this period of music.

I don’t really play video games aside from Civilization VI, so I have no familiarity with Cyberpunk 2077 or it’s soundtrack, but I stumbled across this track from musical duo Let’s Eat Grandma, and I just really enjoy it.

As for The Perfect Girl, ok, I admit it, this one I am familiar with strictly from memes – but after hearing a few seconds of it enough times in various memes, I decided to find the actual song, because it’s so magnetic.

Bitter Sweet Symphony is a classic for a reason – there’s nothing quite like its iconic, endlessly-looped melody, which builds and builds and processes through time and space, and carries with it an indomitable, improbable positivity.

The last three songs are from ELO’s fantastic 1977 album Out of the Blue, which explodes like fireworks crackling across the night sky. This entire album is indescribably wonderful – or at least it is for me.

Music in October 2023

October’s playlist begins with clammbon’s ultimate power-up song, which I would play to wake up in the morning at work. The next song is a similarly swinging piece from the same 2003 album, and yet like much of clammbon’s work, it pairs upbeat and even jazzy instrumentals with heartfelt, at times almost whispered vocals.

Following this are a rollicking rock song from Chatmonchy, Kaho Nakamura’s strange agitations, and The Dø’s windswept Sparks, which sounds like the Aurora Borealis. Then there’s another warm hug of comfort from Hitsujibungaku, another aching and heartfelt songbird’s delight from Yuta Orisaka, and another kinetic lo-fi piano delight from Masakatsu Takagi.

I am going through songs fast today, partly because I don’t have a great way to describe them in words, and partly because many of the songs on this list share similarities, especially as we go on.

Otto Totland’s Solêr sounds as if it was written to be the score of a film where one is waiting in melancholic anticipation, waiting to arrive at a station for a funeral.

I keep slipping ASIAN KUNG-FU GENERATION songs into these, often from the same albums, and that’s how you know I’m consistently listening to all of them, again and again. This track has a particularly fantastic melodic line sawing up and down between the verses.

After this point in the playlist I enter what some might argue is my ‘bad taste’ era. I wasn’t attempting to be contrarian, and I genuinely think all this music is pretty great, but I have learned that some of the more poppy tracks from the ‘70s and ‘80s that I’ve included are regarded as cringe. Well, what can I say – it was a silly era, and I’m a silly guy.

And that’s what much of this playlist is: everything from a Bond movie song to prototypical yacht rocker Christopher Cross; Roy Orbison’s soft-mouthed reveries to downbeat Madonna; even Kenny G! Of course I’ve got the great Kate Bush and Peter Gabriel, but I’ve also included Charlene’s I’ve Never Been to Me, a song that apparently has been voted one of the worst hits of all time. Well, I beg to differ.

Leaving the Cold War, I return to my beloved Humbert Humbert, who has put all their power and gentleness into a song about a lunchbox. Next, a haunting score to metanoia from Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch’s score to Living. Then, I actually broke an informal rule and let Long Time slip in a second time after already including it in the July playlist – but it fits here. And Yorushika always fits anywhere, ready to explode with a combination of aggressive guitars and sweet vocals. Finally, we end where we began, with two songs from clammbon, only this time one is slow and blue, and the other feels benedictory; both seem fitting for an exit, a happy funeral procession in the rain. And isn’t that exactly what October is, after all?

Music in September 2023

Before I had even finished watching the excellent Return to Seoul, I had JungHwa Lee’s haunting 1967 melody Petal lodged firmly in my brain, where it remained for quite some time.

My next obsession was Japanese Breakfast’s 2021 album Jubilee, which has a sort of magnetic pulsating quality – I just got stuck on it. Paprika, for instance, bubbles with rising and falling lines, crisscrossing in a sort of musical plaid. Be Sweet jaunts along with a retro sound pulled out of last century, while the melody of Tactics has the same compelling pull as a vortex in flowing water.

St. Vincent’s Slow Disco feels like raising the curtain on a play – if the play is actually a plain of grass under a rising wind, flecked with drops of flying rain.

The Beths’ Expert In A Dying Field may be a metaphor for a break-up, but as someone who invested years of dreams and efforts to the pursuit of the academic humanities, a field that really does feel in decline, and who did eventually have to call it quits – well, let’s just say the vehicle of the metaphor hits a little close to home. It’s also a superb piece of music.

Another album I got really into was Middle Kids’ 2018 release Lost Friends. Bought It has a rough plaintive quality that works for this sort of earnest rock, and Edge of Town is a total foot-tapping earworm.

I think I mentioned another song from Crash Test Dummies’ 1991 album The Ghosts That Haunt Me Now in a previous post, but it really was a September album (and it feels like one). Both the titular track and At My Funeral function as a gentle act of peacemaking with death, finding comfort in relationships even at the limn of mortality.

World’s End Girlfriend’s new 2023 album, Resistance & The Blessing, is an excellent piece of dark composition, whether that’s eerie piano lines or MEGURI’s demented mechanized waltz.

I had not really listened to Sufjan Stevens much before, but I was vaguely aware of him as an artist I would like. His 2005 album Illinois blew my socks off. This music combines an intense emotional fragility with the anthemic power of a swelling choir. And it also contains probably the best entry in the bizarrely populous subgenre of songs about Superman.

Among John Williams’ many great film scores, it can be easy to overlook the quieter ones, but this would be a mistake. One of my favorites is his warm and tender score to Lincoln. This music feels exactly like the grandly nostalgic and gently patriotic loving imagination of America in the 19th century. It’s impossible to visualize any other place or time.

In September I revisited several different albums from ASIAN KUNG-FU GENERATION, one of the all-time greatest Japanese rock bands, all of which, as they say, go incredibly hard. You just have to listen to them - to any of their work. You’ll be nodding your head and pumping your fists in no time.

Next I included several wonderful pieces of early ‘80s Japanese city pop, a genre of mostly know through more recent remixes used as backing for a very specific subgenre of Japanese cinema and anime music videos. But the original genre is incredibly catchy and fun.

Yokaze, by Itoko Toma, is a classic Andrea pick – a bit of sad piano music that includes all the ancillary noise of the pedals. It sounds like tears falling into a pool of still water inside an echoing chamber.

Kawaranai Mono is the sentimental credits song from Mamoru Hosoda’s 2006 masterpiece The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, and the sentiment definitely works on me.

Enya’s On My Way Home feels like sailing over a sea of warm olive oil, and while that may sound strange I mean it as a compliment.

The last two tracks are from Daniel Norgren’s score to the best film of 2022, The Eight Mountains. Both are elegiac meditations on loss and the fleeting nature of all that we love in this world, yet the music is touched by a kind of sweetness.

Music in August 2023

This playlist got a bit shaggy. In part this was simply a lapse of attention on my part; but it was also and unwillingness to edit. What little I will add in my defense is this: August was a month of albums and long drives on which I repeatedly listened to those same albums, and I had a devil of a time choosing just two or three songs from each, and not the whole thing.

We begin with one of the most exhilarating openings to an album, in this case Electric Light Orchestra’s fantastical 1981 opus, Time. These first two songs, played back to back, catapult the hearer through a time warp into a vision of the future, and they feel like being launched down a luge-track made of hyperspace rainbows. Each time I play this, I find myself compelled to cease all work, turn up the volume, and stand up.

The Barbie soundtrack was, to no one’s surprise, equally eclectic and energetic, from the earworm dance track to defiant punk to Ryan Gosling’s instantly iconic soliloquy of Kenergy.

Completely shifting gears, we’ve got a classical dance from the Pride and Prejudice score, a rawly-sentimental cathartic confession from the appropriately-named Dashboard Confessional, then the wonkaesque clockwork spirals of Kyary Pamyu Pamyu, whose name sounds exactly like her wind-up toy music, and then rerulili’s vocaloid cascade rushing like a slinky on speed down a staircase.

I found Bjork’s collaboration with Dirty Projectors frank-faced and open. And then I did make like a middle-schooler and I went all the way back to MCR. Perhaps it is cringe, but to be perfectly honest they really did have a command of their bombastic and grandiose sound, and I do find it effective.

The next couple of songs are fun alt songs, but Camille’s She Was was probably the best thing to come out of the film Corsage – it methodically and inexorably unspools, and as it plays one sinks deeper underwater.

Long Time is another whisper of bruised hope from Haruka Nakamura, an artist I have become obsessed with over the last few years. Somehow the inclusion of the creaking of the mute pedal adds the same quality to the music that you would get by having an elderly person or a child read verse in a cracking voice. But by the end, the music rises into a benediction, gaining power, glowing in the dark.

Winter Song just feels nostalgic and emotionally full, warm amidst the cold. It’s a fitting representative of an album titled The Ghosts That Haunt Me.

The rest of the playlist is likewise drawn from albums that I became obsessed with, starting with Florence + The Machine’s 2018 High As Hope, which plays out just as its title suggests, with gospel-inspired ascendant spirals of acclamation, split with full-throated emotion. No Choir in particular feels like a bird climbing into a twilit night. I’ll return to this at the end.

Then there’s the album I probably listened to more than any other in August, The Cranberries’ No Need to Argue. The entire album is a raw nerve singing with pain and brokenness, expressed in some of the most beautiful musical terms of the nineties.

For his score to Babylon, Justin Hurwitz echoes his most effective line from the La La Land score, as well as creating several new ones. It’s a heady, jazzy concoction perfect for that particular jaded-yet-adoring view of old Hollywood.

This year, or should I say last year, Sigur Ros released an album that contains some of their best work in years. I listened to it in what I believe to be the ideal environment: on the reddening tundra of the Denali highway at sunset. The image of the shadows creeping over the gilded land, pockmarked with sapphire pools, temperature dropping in anticipation of autumn, looks exactly as this music feels.

In 2022 John Darnielle put out another fantastic album, Bleed Out, filled with darkly defiant screeds. It’s a strange collection of at times threatening ramblings, and it’s a work of typical genius, the musical equivalent of Cormac McCarthy in its particularly America violence.

At the end, I came back to Florence’s album, culminating in a track that makes as good an ending as ELO does a beginning: The End of Love reaches a particular hinge point, when Joshua comes down from the mountain, where the choir that was missing from No Choir crescendos like a mounting cumulonimbus, and I come out of my skin. That’s what music is for.

Music in July 2023

St. Vincent’s work is often brilliant and strange, and this is no exception – an incredibly complex and mesmerizing sonic tide. Then we have two neoclassical pieces that might as well be polar opposites – Shiro Sagisu’s lazy riverboat of a tune, and Jessica Curry’s intense choral fantasy novel of music.

All I can say about Wolf Alice is that sometimes I enjoy brash rude music, especially if I have put some piece of work off too long, and now I finally have got to get around to it at last. But the team up of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs with Perfume Genius produced something truly grand. Spitting Off the Edge of the World actually conveys the feeling of sitting on the rim of one of those grand cliffs in Utah, with a whole desert spreading out below your dangling feet.

Cho Young-Wuk’s score for Oldboy feels exactly like being on a merry-go-round, oddly warm and gentle in its way. Then we have another recording from Toko Miura, who starred in the the best film of 2021, Drive My Car. This music is unrelated, but it has the same sense of pained and sensitive anticipation, like waiting for the cloudbreak on a wet April day. And that cloudbreak comes in the form of another of Takagi’s collaborations with Ann Sally, his go-to sentimental soloist.

Magical Romantic Freestyle is a typically demented work from World’s End Girlfriend, who can always be relied upon to unveil something compelling and twisted. The Young Thousands is also typical of its artist – yet another song from The Mountain Goats which sounds like it speaks directly to the grand sweep of life. I sometimes feel John Darnielle is the lyrical equivalent of Alice Munro. Then we have three frenetic and hurried alt rock songs, each rushing forward, chasing the finish line.

Finally, there are two scores – first, from Living, the excellent remake of the titanic film classic Ikiru. The score and the use of an old folk song both create a sense of holy tension, anticipating the transition out of life. The final score is Ludwig Goransson’s score for Oppenheimer, which will probably win the Oscar – and it may well deserve it.

Christmas 2023

I was traveling in another town yesterday, on Christmas Eve, and so I visited an unfamiliar church’s Christmas Eve service. Sitting in a different context, as an outsider and thus more of an observer than usual, I started to think about the focus on declaring the Gospel as Good News. The fact that the Christian faith is centered on receiving a declarative statement of fact about an external, historical event, seems so encouraging to me. This fact, received and believed, liberates, but the liberation is not achieved or actualized by the hearer: it simply results from receiving the idea. Of course, this is where there is friction for me – I am torn between locating the liberation solely in the work of Christ as external fact, and centering the need for the hearer to respond and believe. There’s a nuance in there which is difficult for me and which causes me a great deal of pain, which I have to acknowledge. Setting that aside, however, I think this emphasis on the Gospel as news is significant. If the medium is the message, then the medium – by which I mean the fact that it is a message – is itself a metatextual signifier that the work of the Gospel is in what has already been done for us. That truth, received, becomes an idea about the factual reality of the world, which buoys the soul with hope. Merry Christmas.

June 2023 in Music

Kevin Penkin’s anime soundtracks have been a revelation – grand orchestrations simultaneously classical and contemporary, and always with some high, haunting crescendo of horns, breaking emotionally – and always with an undercurrent of the eldritch and bizarre.

In June, I got really into Depeche Mode. This is my pattern – there will be some beloved classic artist whose work would always have appealed to me, and yet I will take years and years to get around to them – until I suddenly do. This is exactly the kind of sound I’m ‘nostalgic’ for – a kind of back-projected, learned nostalgia for a past I didn’t have. In other words, a pose. But as far as this type of new wave/synth pop is concerned, I’m shameless.

The next three songs are also from that same time period, but they’re otherwise quite distinct – contrast Bjork’s squawking cries, all rough edges, with Ultravox’s ultra-smooth sound, as if they’d taken a sander to their music. And of course Peter Gabriel is just my favorite.

After that it’s more oddness Mili, and then more J-Pop, and I’ll just specifically shout out ZOMBIE-CHANG’s terrific vocal style. She manages to sound incredibly droll and utterly done with everything, in a way that adds character to the music.

Then I decided to revisit 2014, when I listened to the radio on my commute and enjoyed WALK THE MOON’s optimism – and you know what, it’s not a bad thing from time to time.

Junkie XL pulled off a gently haunting score for Three Thousand Years of Longing, not really what you’d expect from the Mad Max guy.

Late Yellowcard is still pretty good, despite what some folks might say.

Fly-day Chinatown is perhaps the greatest example of early ‘80s Japanese city pop, and it was probably my song of the summer – indescribably grand.

May 2023 in Music

Of course we begin May, the crowning glory of spring, with Takagi, who is always gentle and warm. I think a lot about gentleness; I feel that we encounter God in the gentle beauty of small things, like dew on a flower or the pre-dawn chatter of birds. But saying that comes with its own doubtful anxiety, because in seeing God as gentle and near, immanent in the beauty of creation, I tend to also interpret that as a sort of universalistic or unqualified reassurance, which sits in tension with my understanding of theology. For me, this is a sort of veil between myself and fully experiencing the sense of safety and peace betokened by small, beautiful things. But I do think that the nearness, the immanence, and the gentleness of God in creation is indisputable, regardless of my confusion.

Ok, I admit I revisited Born Slippy because my favorite film podcast did an episode on Trainspotting. Otherwise this seems a little incongruous for me. But it does fit with my listening in one sense: it’s some real fin-de-siecle stuff, rattling around the great empty echoing chamber of the end of history.

Clammbon put out a new album this year, and twenty years into their career they haven’t lost their step, and no one sings with quite that specific sort of strange plaintiveness as Ikuko Harada.

I went to see Guardians 3, and there’s a sequence where they play some diegetic music which is meant to be alien, to sound like nothing ever before heard on earth – but being me, I immediately recognized it as Vocaloid Japanese music, and looked it up as soon as I left the theater. Make of that what you will.

I’m Always Chasing Rainbows – this was another from the soundtrack of Guardians, and it’s an example of how I’m very basic in respect to big swelling rock chords. As for Ancient Dreams, Marina just never misses the opportunity to be musically striking. As for Mili, I honestly don’t know how to describe their music – but I like it. I stumbled onto Mallrat in May, and just kept circling her music. And of course, Pacific Coast is just pure highway cybervibes.

Purple Clouds, however, is quite something. Kensuke Ushio weaves a delicate ending to Naoka Yamada’s stunning television adaptation of the Heike Monogatari, and this score plays over the final thesis of a story which concludes that the only response to death and loss is to pray and remember. What else can we do?

April 2023 in Music

As before, I’m just going to highlight songs I have something to say about, not go through every single one. For me, the rewarding thing is actually making the playlist, which serves as a snapshot of what I was listening to at the time.

I love Peter Gabriel, and I found his score for The Last Temptation of Christ haunting and weird, with all the mysticism that term implies. In particular I became fascinated by the track It Is Accomplished, which drops a set of tubular bells down a staircase to announce the final break of tension, the catharsis of the world. Jerry Goldsmith turned in a surprisingly classical, old-Hollywood overture for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (a film I personally had underrated). The lush strings sound like they could belong to a golden age picture. Florence + The Machine’s Between Two Lungs is about building up steam until achieving a sort of runway, breakneck pace – and that’s perfectly typical of her music, and why it works so well.

I’m a La La Land defender, but if the movie suffers from anything it’s that its first two tracks are so much better than anything else in the film. There’s a sort of traveling line of melody in them that is a complete earworm and came to dominate my brain for several weeks. I’ve always found Janelle Monae an undeniably great talent whose work is always catchy, and St. Vincent’s Nowhere Inn is a welcome addition to a subgenre of southwestern-inflected music that is both warm and bleak.

For his film Suzume, Makoto Shinkai wisely brough RADWIMPS back for the score, and they in turn brought in Kazuma Jinnouchi’s eerie cyber-choirs to create the score for an movie all about eldritch locations.

I love The Sundays, and I found that Summertime is upbeat, but it insists on happiness in a sad voice, whereas Cry is melancholic in a contented, almost satisfied way. Finally, Tanukichan’s And More is an all-subsuming flood tide of composite warm noise.

March 2023 in Music

I’m making a concession to reality – something I greatly struggle with. I can’t stand admitting that time is limited, and that I’m simply not going to do everything I planned in the way I planned in the time I planned – but sometimes it’s impossible to maintain the illusion. So, I’m going to post my playlists for each month, but I’m only going to comment on the songs I feel like saying something about, and only briefly – I’m not going to attempt to conjure up whole paragraphs about each, because I simply don’t have that much to say, and because trying to do so has delayed these posts to a ridiculous degree.

Having said that, here’s some of the music I enjoyed in March:

The first thing I noticed, revisiting this several months after making the list, was that between Sum 41 and Reliant K I appear to have been nostalgically revisiting high school, which is not a bad thing to do when it comes to music. When you’re young it can be easier to accept openly emotional music without trying to critique it through the filter of sophisticated taste. Sum 41 in particular reminds me of the time when punk Naruto music videos on primordial youtube were the height of sentimentality.

And let’s be honest, sentiment or aesthetic sensation is, at the end of the day, the whole explanation for the inclusion of any song. Sometimes it cuts through regardless of what a song is actually about. Rocky Mountain High is a beautiful hymn to the beauty of nature, even if I’m deeply opposed to the idea that bringing more people to a place is a bad thing. Can a song be misanthropic and also beautiful? I suppose it can.

Everything CHVRCHES puts out reliably serves to help me cut through the mental fog of a tired Monday morning, Just Like Honey is yet another example of an end-of-century warm fuzzy mass of sound that I like, and Humbert Humbert continue to do variations on the same musical themes and emotions. Personally, their music makes me feel they are gardeners gently tending to a tiny, delicate crocus (I am the crocus). And Saho Terao’s music slipped into my feed and was immediately slotted into my ever-expanding collection of teary Japanese music.

Carter Burwell’s True Grit score is a rousing yet understated accompaniment to what might be the Coens’ finest work. And yes, in 2023 I finally discovered Jamiroquai, thanks to memes. The next couple of tracks showed up on the excellent soundtrack for Licorice Pizza, and sparked a minor obsession where I would play them every morning while I commuted for about a week or two.

After that come three excellent pieces from film scores, another hopeful work from Hitsujibungaku, an admission that yes I do like bagpipes, and a Takagi which reminds me of the time I was a child staying at a motel in Australia, and through the evening humidity and the symphony of cicadas came the flashes of distant lightning, and the approach of a glorious summer storm.

Alaska Summer 2023

I arrived in Alaska in the middle of June. Since then, I’ve been learning my new job, getting to know the good people I work with, and settling into my apartment, neighborhood, and now, church. But I’ve also been cramming as much mileage on my car as possible and taking all the pictures I can. I’m blessed with a short commute, so during the week I don’t drive very far. Instead, I have redistributed all that mileage to the weekend, in an attempt to probe just how far you can reasonably get in a single day. My only wish is that there were more roads to drive down – for being the largest state in the Union, Alaska only has a few highways.

There are, in fact, only two ways to leave Anchorage – you can go south on the Seward Highway, or north on the Glenn (and technically on the Old Glenn, but that’s almost the same thing). So, over the first couple of weekends, I probed south, along a road which hugs the broad tidal flats of Turnagain Arm, which separates Anchorage from the Kenai Peninsula. At the end of the Seward Highway is, well, Seward, the town named after the great Secretary of State who arranged Alaska’s purchase, and who is one of my favorite American politicians. Near Seward is the Exit Glacier, which is itself merely a tiny protuberance of the much larger Harding Icefield. If, instead of going to Seward, you turn onto the Sterling Highway and drive about 140 miles further, you will come to Homer, a town built on and around a spit of land jutting into Kachemak Bay. When I was there, the mountains just across the bay seemed to be emitting a strange cloud of fog or dust which almost seemed to glow.

For the long weekend of the Fourth of July, I turned North. Just northwest of Anchorage, the Matanuska Glacier creeps across the valley floor, bizarrely lower than the highway, a monstrous incongruity of ice. Continuing on, I turned south, slipped through a darkly verdant canyon of hanging glaciers that seemed to exhale clouds and equally white waterfalls, and came to Valdez. If you look at the third picture below, on the right you’ll see the modern port and on the left the terminus of the Trans-Alaska pipeline, from which oil is shipped out through Prince William Sound. It was there, just a few miles out of Valdez, on Good Friday, 1989, that the Exxon Valdez ran aground and spilled its cargo into the sea. And, in the foreground of the photo, you can see some of the land on which the town used to sit, before it was destroyed by subsidence in the 1964 earthquake, the most powerful ever recorded in North America. As a consequence of the earthquake, the entire town was relocated. This earthquake, of course, also took place on Good Friday.

I did a silly thing, leaving Valdez – I treated it as a short detour on my way further east, and tried to reach McCarthy, which sits at the end of 60 miles of dirt road, the extremity of another road. I tried to reach it in the same day in which I had left Anchorage and visited Valdez, and I almost got there (though it would have been very late). Unfortunately, bouncing along the potholes, the seal on my oil pan came loose, and I suddenly discovered there was an indicator light on my car that I’d never seen before. Fortunately I was able to make it back to Glennallen where there is what has to be the busiest gas station in the state. Having thus altered my plans impromptu, I slept in my car for a couple of hours, and when I stepped outside for just a few second, I found myself immediately covered in vicious mosquitoes. They are somehow even worse than described.

As I proceeded north up the Richardson Highway, I discovered the reason why. It turns out that the typical interior landscape of Alaska is a series of enormous ponds and marshes, stretching as far as the eye can see, and incubating untold trillions of mosquito eggs. But just a little further, and it all became worth it, as I crossed the Alaska Range, and saw its brilliantly-colored slopes. And there, in front of them, like something out of a dream, ran the pipeline. I wasn’t surprised to see it, of course, but I still wasn’t quite prepared for how strange it looks, like an alien spacecraft landed on earth. And it just went on and on, without ceasing. It reminded me of the Great Wall receding, ridge after ridge, into the hazy distance.

I stayed in a small cabin in Delta Junction, and I was thrilled to discover myself in the landscape that has so long fascinated my imagination – the endless birch woods of the north. I imagine the Sweden of my ancestors, I try to imagine medieval Russia and the river routes to Byzantium and Baghdad, and I cannot imagine the vastness of Siberia, try as I might. But these woods are a picture of it.

The following day I headed south again, but this time I turned off to the west, to cut over the highlands on the Denali Highway, over a hundred miles of dirt road that mostly runs over land just barely too high to grow trees – which is not as high as you’d think. To the north, under the louring sky, gaps in the wall of mountains opened here and there to disgorge colossal frost-giants. Across my path, rivers unspooled like silver threads on green silk.

After that weekend, I decided to stay closer to Anchorage, so I went up to the Independence Mine, an abandoned mining town which is now a public park. It wore a forbidding aspect, as twisted and broken mine cart rails hung in the fog and rain, and it was difficult to picture as it must have been, filled with people and bustling with life.

I have a fascination with glaciers, and as soon as I became aware of the Exit Glacier trail, I knew that hiking it had to be a top priority. The trail starts almost at sea level, in the birch forests along the river coming from the base of the glacier. From there its stone stairway climbs three thousand feet up, skirting the edge of the Exit Glacier. The summit holds the prize: an unbeatable view into just a portion of the vast Harding Icefield, which extends beyond the horizon. There’s nothing quite like gazing into a vast sea of ice. I even spotted a tiny figure walking across a part of the ice; you can see them in two of the pictures below.

The problem I ran into was not ascending the trail, but descending. I had not done a hike like that in a couple of years, and going down the stone stairs I was beset by terrible leg cramps and fits of shaking. Fortunately I had plenty of daylight to burn, and I was able to use the distended descent time to listen to a fascinating history of Stalin’s gamesmanship of the Central Committee in the early ‘20s. Of course, I don’t know if I can use that term in the same way any more – after all, we are now in the early ‘20s once more. And the whole way down, the glacier glowed an intense blue in the evening sun, tempting me to toboggan down it.

Alaska was a Russian colony before it was purchased by Seward, and I visited some of the beautiful Russian Orthodox churches that dot the Kenai Peninsula. In the village of Nikolaevsk, settling in the 1960s by Old-Rite Russian Orthodox, I even found an onion dome sitting on the grass, like you’d find a car in other rural parts of the country. Perhaps it was being patched up to be reinstalled somewhere.

On a different weekend, I traveled north to Denali National Park. Staying in a cabin next to a pack of sled huskies, I got a taste of the extended lilac hour, which in the Alaskan summer last much longer. The next day, I rode a bus into the park. Though I never got a clear view of the mountain due to its perpetual cloud-cover, I did see two bears, some wild sheep, and a landscape that looks like my romantic imagination of the Mongolian steppe.

One thing I loved about the summer was the proliferation of bright flowers. Here you can see a few of the ones I encountered, along with your typical ferny underbrush. The explosion of poppies is my nextdoor neighbor’s wild garden, and the low pink groundcover was spotted at the top of the Exit Glacier, where the dark stones were so warm from soaking up the sun that I laid down on them for a while. There’s a picture of Anchorage from above, and one of my favorite type of wildlife – the bumblebee.

I made one final trip that summer, and finally completed by journey to McCarthy. Along the way I crossed the Copper River, traveled through the some of the most glorious country I have seen, and finally came to a tiny town at the end of the last road. A couple miles uphill was the creaking ruin of the Kennecott Mine, which for thirty years was a bustling town with families and children and trains to the coast – and then just as soon as it appeared, it was all gone. But the ruin is incredible, and it sits just above a vast glacier, which appears like so many hills of dirt on the march. Just north of the mine, past fields of glowing fuzz, I was able to step onto the icy toe of the Root Glacier. My typically poor planning (or improvisational style, if you prefer) had left me unshod to go any further – but there’s always next time.

Krakow

When I left Auschwitz, I had to double-back to Katowice, going the wrong direction – that was the only way the train would go. It seemed the place did not wish to let me go; the ticket machine was broken. I was nervous about trying to buy a ticket on the train, speaking no Polish and being generally shy and very self-conscious about always following every rule, at least when abroad. Fortunately, I had met a young Bulgarian on the tour of the camps, who was in the same boat as me, only more at home on eastern European trains, and together we made it back to Katowice. He seemed a very nice fellow, and he explained to me that he controlled the stoplights in some midwestern city (I think maybe Oklahoma City, or perhaps Omaha) from his office in Sofia – a funny reminder of how tightly interlaced our planet is today. I wish him well.

From Katowice it was only a short ride to the east to Poland’s ancient capital, Krakow. When I arrived the city was grey, under November clouds, but as the light went out it became a place of high contrast – pitch black side streets opening onto brilliantly lit thoroughfares crowded with streetcars and buses, and lots of people walking here and there, eating street food in the subway underpasses.

In the morning, I rose and went out, and it was a bright and sunny day. I was staying on the southeast side of the city, in Kazimierz, what had been the old Jewish quarter of the town. The first sight I saw going down the street was the Remah cemetery, quiet and overgrown with green, even in autumn.

From there, I walked up a path that climbed the Wawel hill, the ancient castle of the kings of Poland, wrapping around it like a spiral. From the bastions, the view of the Vistula, one of the great rivers of Europe, was incredibly peaceful, and the brick towers were clomb with ivy, like some New England university.

Inside the castle was a hodgepodge of buildings of different ages, all run together around a grassy courtyard where the garden was planted among archaeological ruins. The crowning jewel was the cathedral, and over the gate hang the famous bones of the Wawel Dragon, which have decorated the cathedral for centuries. Dragon or not, the bones themselves are quite real, and are probably the fossils of either a whale or a mammoth.

Unfortunately I could not photograph the interior of the cathedral, a gorgeously baroque space of green marble and gilt decorations. I did climb the belfry, up ladderlike stairs squished between the gargantuan wooden trellis of the bells – and I’m glad those bells were silenced with wood beams, because they would have deafened me. Each bell was bigger than my car.

Then I passed down into the city, past the statue of Poland’s favorite son, John Paul II, and up the many cobbled streets, past ancient churches and vendors selling tourist knick-knacks, to the great market square and its famous cloth-hall, the Sukiennice.

There in the grand square, perhaps the greatest I had seen in Europe, a group of Ukrainians held vigil by a fountain, extolling their country’s plight, and, I presume, asking for aid (unfortunately I do not speak Polish or Ukrainian). These countries, once frequent rivals, are now knit together in solidarity. From time to time, as I wandered the square, I would hear them play music, echoing off the colorful facades, lamenting.

Then I walked to the north end of the city, to one of its many narrow gates. The wall is beautifully intact, the towers still high and proud, and the barbican stands before the gate in the joggers’ park that was once the city moat, no longer warding but welcoming.

Slowly, I made my way south again, past a group of vans behind the train station which seemed to be intended to help Ukrainian refugees in some way, perhaps with document processing – I could not be certain. I crossed the Vistula on a bridge flecked with frozen dancers, and there, on the south side, I stopped at two pilgrimage sites. First, the Apteka pod Orlem, a pharmacy whose owner and staff did all they could to aid the persecuted Jews in the ghetto there during the occupation. Then I went to the famous factory owned by Oskar Schindler, which served as an ark for many lives.

At night, the great market square, the Rynek Glowny, became a place of unsurpassed beauty, as the streetlights flared off the cobblestones.

Movies I Saw in 2022

Ok, I’m laughing at myself as I start this one. I’m not sure how many times I can make the joke about me posting something late, but in this case I almost have to. I meant to write this blog at the end of 2022; it is almost Halloween of 2023. Oh well lol.

I want to be very clear, this is not a list of films released in 2022 – I’m going to get to that in another post. I’ve also mostly excluded films released in 2021, because then it would be too heavily dominated by recency bias, especially since 2021 was a banner year for movies. The only thing these movies have in common is that I happened to watch them, some for the first time, some not, during 2022. I’m only going to run through a few titles here that I wanted to mention for one reason or another. In total, I watched 216 movies in 2022.

My Neighbor Totoro

I started the year off right; on January 1, I watched Hayao Miyazaki’s beloved classic, My Neighbor Totoro (1988). This is part of a subgenre of movies that depict rural Japan and which therefore crystallize a very specific sort of nostalgia for the brief time I spent toodling around the chequerboard fields of Funakura. Totoro is a sort of bright mirror, however, because my nostalgia is melancholic, recognizing my own peculiar adult faults and remembering a time where I was both very relaxed and happy, but also often lonely and sad. The film, on the other hand, depicts childhood joy in a way that seems innocent and free. Even so, it’s a film about children facing, in some small way, the anxiety of loss, which is why it has far greater staying power than a lot of other films aimed at children. It’s hard to see a way back to this sort of childhood joy, but I think it’s necessary to believe it’s possible – perhaps to return, to come, as Christ said, as a little child.

Other notes:

· Joe Hisaishi’s scores are always iconic, but this one is particularly magnificent, as anyone remotely familiar with it knows.

· The world is strange and twisted in a sort of unsettling-comforting unity. Cf. Catbus.

· This is the cinematic equivalent of “All shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.”

Germany, Year Zero

Only a week into the new year, I watched Roberto Rossellini’s stark film, Germany, Year Zero. Released in 1948, only three years after the fall of Berlin, the film takes place in the broken rubble of the desiccated city, and follows a child as he attempts, somehow, to live in a world of shards and ash. Personally, this film challenged the limits of how I think about the world, not because anything in it was surprising (I’ve read plenty about the period), but because I had to confront the fact that there didn’t seem to be a way to act correctly in such a situation. I tend to obsess over what people should do in any situation, how things should be – and Berlin after the fall laughs and spits in the face of such thoughts.

· This is a case of melodrama being fully justified by the actual state of things.

· This is a real case of that standard of fiction, the work that tries to picture what would happen to survivors of the apocalypse. We just usually like to look away from times when that actually happened.

· Part of the tragedy is the image of children with no hope, made even more poignant because, in the light of history, we know that there would eventually be cause for hope, and other things to live for. But I know how hard it is to see that in your own life, even in cases where you intellectually know it to be true.

The Worst Person in the World

I said I wouldn’t write about any films released in 2022 or 2021, but made that rule intending to break it for two movies, just to make a point about their greatness. The first is Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World. This is a strikingly beautiful movie (Oslo is filmed suffused in faded natural magentas and lavenders), and Renate Reinsve gives an astonishing, gentle performance. But more than anything, the film directly addresses my anxiety about wasting my life, and being a small, selfish person. And it reaches a profound and inexplicable state of catharsis, without fantastically compromising the reality of life depicted. If you read a synopsis of the plot, it wouldn’t sound like anything special, but that’s simply a testament to the importance of execution and direction. As it stands, this is one of my favorite movies.

To be completely honest, I don’t know how to relate to catharsis in art. I think that we desperately need it, or at least I do, personally – but my fear is that I arrive at a purely emotional sense of relief, and believe that all will be well, without that necessarily involving spiritual reconciliation. That seems sort of cold to say, and I’m not happy with that doubt; but I think this struggle of whether or not to doubt the cathartic impulse of the moment is, for me, of a piece with the struggle over limited or universal reconciliation and redemption, and that’s not something I’ve really resolved within myself. So when I encounter art that strikes the chord in my soul that echoes Little Gidding’s refrain that “all shall be well, and/all manner of thing shall be well,” I worry that I’m rushing to just accept a Gospel with no demands. But it is, on the other hand, a free gift. And Tolkien wrote about the sudden unlooked for turning, the surprising moment of positive resolution, and I think this feeling is in that tradition.

If that seems like a rambling and personal tangent, perhaps it is – but it’s the thing that most nearly intersects with my own life, and in that way it’s the thing that I have got to say. There’s a mirrorlike quality to the film, at least for me. In the scene were our heroine tears up, looking into the dawn, I felt the shock of reminiscence – I too have climbed the rocky hill in order to be able to weep joyfully into the dawn.

Phantom Thread

Another softspoken movie I saw, perhaps one of the most softspoken, was Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2017 film Phantom Thread, which I will not attempt to define in terms of genre or plot. It’s both very simple and extremely strange, and I think it’s a career high performance from Daniel Day-Lewis, which is matched by Vicky Krieps – a true battle of megawatt performances, conducted almost in whispers. This is the best PTA movie I’ve seen, a film with rich visual textures, a specific quality of light, the calm essential vitality of being. Everything is exactly right.

A Story of Floating Weeds/Floating Weeds

I’m cheating a little with the next, because I watched Yasujiro Ozu’s A Story of Floating Weeds (1934) in February of 2022, and then watched his 1959 remake of his own movie, Floating Weeds, in February of this year. The two have the same plot, and they are both superb. Ozu seems to have cracked the code, realizing that the best way to prevent someone from making a mediocre remake of your movie is to just make a great one yourself first. While the remake is more dynamic in some respects, and has the benefit of glorious Agfa red, a color God decorates heaven with, I actually felt more emotionally moved by the earlier film, especially by Emiko Yagumo’s tremendous mouth acting.

The Passion of Joan of Arc

Another extremely emotional black and white film I saw in February was the 1928 silent masterpiece of Carl Theodor Dreyer, The Passion of Joan of Arc. The film depicts Joan during her trial and, if you’re so inclined, martyrdom, and features the most and probably the best eye acting I have ever seen, from Maria Falconetti. The film is a fragile yet unvanquished image of defiance in the face of sneering, mocking evil, yet without the sort of romanticized erasure of human frailty and fear. I’ve always been scared by stories of martyrs, because I just don’t think I could endure such a trial. And yet, in this film, Joan remains human while becoming a saint.

Lady Snowblood

On a completely different note, Toshiya Fujita’s 1973 revenge classic, Lady Snowblood, is a luridly vivid splash of crimson blood that just rocks. But there’s a tremendous amount of artistry present in the design and direction – there are incredible shots of stunningly white snowy foregrounds within an inky void of black negative space – and into that, the reddest blood imaginable.

Millennium Actress

Satoshi Kon is one of the most beloved directors of animation, who passed sadly long before his time, after directing only four features. In March of last year, I watched all four in a row, and of those four, Millennium Actress is my favorite. The film is a nostalgic collage, blending memories from the life of the eponymous actress with fictive temporalities plucked from her movies. It’s a meditation on the way in which we construct our own nostalgic pasts, whether for gratitude or regret (to the extent that, in nostalgia, they even differ), and paste our memories and created stories together like newspaper cuttings. The imagined relationship that could-have-been becomes a sort of parasocial love affair with one’s own remembrances. The film creates the feeling of age, the sense of astonishment that a life can span so much time, so many different worlds; but it doesn’t only look backwards. Somehow, despite its fascination with nostalgic longing, with might-have-beens, the movie is robustly hopeful in ultimate outlook, and is all the more successful at cheering me up because it feels honest in its treatment of life.

Drive My Car

I said I would break my rule against 2021 releases for two movies, and the second is one which I have watched at least three times since its release, and which has now got the better end of the tie with Worst Person in the World for my favorite film of 2021: Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s monumental Drive My Car. There’s a lot of things to say about this movie. First, the titular car is one of the best-looking vehicles I’ve ever seen in film: a red Saab 900 Turbo. They don’t drive it fast (it’s Japan), but they drive it oh so well.

Second, this has the same thing going for it as Worst Person in the World, to the extent that I view them as somehow twinned. This is a movie about catharsis, about accepting that despite life not being what you hoped for or expected, and despite the wounds we wear, you will be ok. In some respects, this film is even more directly about that than the other, and so of course I can’t even really fully feel that sense of catharsis, without simultaneously feeling doubt – because the way I apprehend catharsis feels like a cheat, like smuggling in the attitude of implicit universalism, or a release from moral risk and responsibility. But I hope that one day, I shall be whole, not perfect, but able, at least, to feel that catharsis and peace when watching a movie like this, and not second-guessing.

Finally, the film has an incredibly cast, all of whom give fascinating performances. I think a lot of people have noted Reika Kirishima as a showstealer, and she is a strange, cryptic presence. The two leads, Hidetoshi Nishijima and Toko Miura, give performances that are all the more emotionally potent for their restraint, for what they do not say. I went into this knowing Miura as a musical artist, and I was surprised and fascinated by her character and presence. But the person who actually stole the show for me was Park Yu-rim. She delivers the culminating monologue of the film, a speech from Chekhov’s play Uncle Vanya, in Korean Sign Language, and in that scene, in near complete silence, the film fully articulates its message – that, acknowledging our pain, we still must live our lives in quiet hope. It’s maybe the best performance and definitely the best scene of the year, and I can’t stop repeating it, because I desperately need the seed of hope amidst reality that it contains.

Last and First Men

I also watched one of the best movies I’ve fallen asleep during (in fairness, I was very tired): Last and First Men. I first became interested in this because I stumbled across the music, composed by its director, composer Johann Johannsson. Sadly, this film was the culmination of his career, as he passed at a young age, so this is also his last and first film. I was so intrigued by the trailer that I read the book as well, a narrative of an imagined distant future, spanning eons of time, written a century ago by Olaf Stapleton. The film boils this story down to a spare monologue of narration by Tilda Swinton (of course). This plays over a series of still black and white shots of decaying concrete Communist monuments. And there are frequent pauses of a minute or more, in which the camera does not shift and the narrator does not speak.

In short, it’s improbable and surprising that this movie works – but somehow, it does. The central arc of Stapleton’s book is a civilization trying to cast about for any source of hope or meaning in a cold, bleak universe, where entropy will eventually run the clock out on history. Johannsson managed to find the perfect way to represent the epitaph of hopeless time in the monuments of a failed regime that gestured toward a better future. It’s haunting and beautiful, even if it does put you to sleep. Having said that, I’m glad I don’t believe in a universe in which the cold heat death of material processes is the final word on life.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

Peter Weir directed the second-best movie of the 1970s, an esoteric, meditative play of soft light and sleepy, otherworldly vibes. But that’s not what I’m here to talk about, because in 2003 he also directed what must be the greatest tall ship movie of all time, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World. I have extremely complicated emotions about the British Empire (a villainous enterprise of exploitation that created the world in which a disproportionate of the culture I grew up with and have nostalgia for was created), and by extension, the Royal Navy, but my emotions about this movie are extremely simple: it’s great! Part of it is that I love movies that show professionals at work, executing processes with aplomb; part of it is probably that the RN is the prototype of my beloved Starfleet, the example par excellence of that sort of professionalism (it helps that Crowe has a Shatneresque energy to him). I think ultimately, there’s nothing as romantic as a tall ship on a wide open sea.

Boyfriends and Girlfriends/Four Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle

In short succession I watched two of Eric Rohmer’s little films (I use the term affectionately, not pejoratively), Boyfriends and Girlfriends, and Four Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle. I feel like these quiet pieces, in which little seems to happen except for ordinary life, with warm colors and a gentle spirit, are mining the same vein as Ozu’s later work. I also have a very strange nostalgic fascination with western Europe in the 1980s, possibly based on architectural books I read as a child, and these films fit nicely into that grain.

The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun

In May I watched The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun, a film by the great Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambéty, and this short movie feels like some sort of perfectly cut topaz or amber gem. The whole is encapsulated in the part, in one sequence when the characters go dancing down the street in a way I can’t really even describe – but it’s electrifying.

Atonement

I also watched Joe Wright’s 2007 film, Atonement, which I had been meaning to get around to for a long time. For me, it’s a fascinating collision of nostalgia and antinostalgia; longing for worlds which never got to exist, and, at the same time, rebuking that with harsh reality, nostalgia collapsing into guilty regret, and all played out against the backdrop of a wartime England that is, for many like me, a site of great nostalgia, but which was also at the epicentre of the ultimate collapse into imperial guilt and regret. It’s also a gorgeous film, which includes one of the most successfully elegiac sequences I’ve ever seen.

Dodes’ka-den

Everyone loves Akira Kurosawa, and I’m no exception. Working my way through his filmography, I came upon Dodes’ka-den, and was shocked that the great director had made something simultaneously so artistically compelling and successful, and so – well – ugly. I thought I knew what sort of films Kurosawa made, and was very comfortable with them, but this was jarring and nauseating. It’s never going to be one of my favorite of his films, given my sentimentalist, cathartic biases, but I’m going to remember it with great respect for the truth it depicts.

The Virgin Suicides

The Virgin Suicides is as good an argument for nepotism as you can make. Personally, I think it’s probably Sofia Coppola’s best work. It manages to crystallize an incredibly specific sort of narrow hopelessness one gets in adolescence, when you can’t actually see a path into the future. To the extent that this is the condition of mortal life, it’s a universal text, even though all is portrayed through an extremely particular suburban moment.

Juno

When I watched Juno, I had no expectation that I would be so thoroughly won over by it, but the film is so winsome and charming that I had to watch it a second time in short succession. It’s the perfect combination of wit and sincerity. And for all that this is a dialogue-driven film, the most powerful line in the movie is read, not spoken. What an optimistic little movie!

Silence

I think the greatest and most profound movie I saw in 2022 was Silence, a movie that so transfixed me that I not only immediately read the novel it was adapted from, but also read someone’s dissertation on the hidden Christians of the southwestern islands of Japan. In my view, this is Scorsese’s best film, but that’s not the most surprising thing I could say – this movie was designed for me in a lab. It combines calling out to God, trying to hear Him respond, with deep practical theological angst, and all of that through a beautifully reconstructed early Edo-period rural Japan. I don’t have the same sort of complex the protagonist does, but I remember in childhood being anxious about the idea of tests of faith in martyrdom. I’m not even sure what I think about what the film seems to be suggesting about pride and martyrdom, or mercy – I think I may actually not agree, if I’m understanding it correctly – my view of the potential value of martyrdom is perhaps not deconstructed much at all. But I love the incredible sense of empathy the film has, and as a weak person, it seems to be begging for room for those of us who are weaker. And, without spoiling anything, I will say that I have often been sitting and thinking, and the final shot of the film will come unbidden to mind, and I will begin to cry.

Andrew Garfield should have won Best Actor for this, and someone in the staggeringly good cast of supporting actors should have also walked with an award – take your pick as to who.

Paris, Texas

Paris, Texas honestly wasn’t doing that much for me for most of its runtime. I could tell it was well-crafted and looked nice, but it just wasn’t connecting – until the end. The last conversation through glass really broke through to me, and I was left reflecting on a story about what love is after you feel you’ve lost your right to it, yet still find it extended nevertheless. It’s a picture about grace.

Days of Being Wild

Days of Being Wild, another Wong Kar-Wai movie in which the director wonders what would happen if everything was teal, is a film where you can actually feel and smell the humidity as you watch it. And it captures the dread anxiety of knowing that you’ll hate yourself if you do something that you’re nonetheless drawn to, even as you feel anxious that you don’t want to hate yourself. Possibly his best film I’ve seen? I really will have to think about it.

Whisper of the Heart

Whisper of the Heart was made by Yoshifumi Kondo, the man trained to be the successor to Miyazaki and Takahata at the head of Studio Ghibli, but he tragically died after only directing this one feature. Miyazaki has made 12 movies; Takahata made about 7, I think. Yoshifumi Kondo only ever got to make one. His movie is as good as the best movie from each of the others; it’s on par with the best thing any anime director has done.

You might not believe this, but it's true: near the beginning of this film I paused because I was sad and discouraged, by two specific feelings, not because of this film but occasioned by its hopeful sentiment. First, that my life would never make sense like a story does, and second, that it has declined, and I no longer enjoy things as I did, or am as good as I was. Then, almost halfway through the movie, our heroine voiced exactly those same feelings. Now, maybe I have more cause to be anxious about life not making sense, since I'm much older, but still, it's something. This is a deeply hopeful precious gem.

A Hidden Life

I watched Malick’s A Hidden Life alone in a room in the Catholic center for dialogue and prayer a block away from Auschwitz. It seemed the right place for it. Once again I feel that Malick has perhaps the best grasp on the Beautiful and Good of anyone working; he also has the strangest way of editing conversations I’ve ever seen.

Talking about our comfortable idea of Christ, as opposed to the Man of Sorrows, and thinking about how we live, and try to avoid suffering, is really challenging for me, and speaks into a lot of my anxiety about what I should or shouldn't do, but don't. I struggle with heroic narratives because they suggest a higher moral possibility than I want to have to contend with. I just have a lot of anxiety about the consequence of the divide between people who will die for the truth, and those making excuses not to, since I feel like someone who makes excuses to do the easy thing.

Moulin Rouge!

I realize that Moulin Rouge! elevates adolescent feelings and crushes to the level of something noble and true in a way that doesn’t fully pass scrutiny, but it’s just done so compellingly and with such unembarrassed sincerity that it always wins me over. It’s both a sentimental picture of romantic, emotional love defeating cynicism, and a deeply comic film in which a coquettish Jim Broadbent grunts out Madonna lyrics (he should have gotten an Oscar for this).

First Reformed

On First Reformed, a film I took very seriously but was deeply puzzled by: I have never quite known how to process really serious arguments about the warnings on climate change, because it's such a challenge to my own desire for optimism and my rootedness in the idea of the status quo, the idea that some things get worse and some things get better, and it all evens out and we muddle through like we always have. I know that there is a religious and eschatological answer to all of this, which I believe in, but it's difficult to foreground that because of my own anxieties about eternity, and because of my reaction against the end times obsession among Evangelicals when I was growing up. Maybe all of this is just the recognition that while I believe the climate models and think more needs to be done, I’m less willing to significantly change my lifestyle, and unwilling to ask others to forgo ascension into the middle class, so maybe I'm just unwilling to do triage, so firmly do I have to believe in a possible future that is better than the present, and not worse - and now we're back to eschatology and eternity, and the fact that we're all deluding ourselves the moment we forget Death. But we also must live here, now, and our children. And I will say this: I’m not really an activist, and I don't tend to support radical sacrifices. I don't support denying the developing world power, and I don't support seriously reducing the middle class lifestyle, although I worry about how that interacts with my Christianity, given Christ's call to deny ourselves - but I don't want to fall into a kind of Puritan impulse to sacrifice for its own sake, that life has to be hard. And I will also say that I think it is good to bring children into the world, even this world. But this all just sets off my anxiety of conviction - in church they say we have to change, and I feel unwilling, and am anxious, and in the political sphere activists say we need to change, and I feel unwilling, and become anxious. It's tiring, although maybe that's an excuse. I think I've just never really been able to get around my sense of anxiety about certain kinds of disruption, perhaps because there's no clear limit to it, or perhaps just because I don't want life disrupted with no sense of control over it. And I think I've never fully been able to get on board, because while I can be appalled by the destruction of the forests, I always am thinking about civilization and its maintenance, and there's a part of me that worries it doesn't work if too much is changed. It's like when people started singing about removing dams - immediately I thought, "dams are important, though - you can't realistically impound enough irrigation water for droughts without them." But I worry that makes me a bad person. I think that cui bono is the right question, and I think the distinction between me and some folks a little further to my left on this is that some of them would focus that answer on large corporations and the holders of global capital, while I am always worried that actually, it's not just them, it's all of us, too. And I have no idea what to make of the ending.

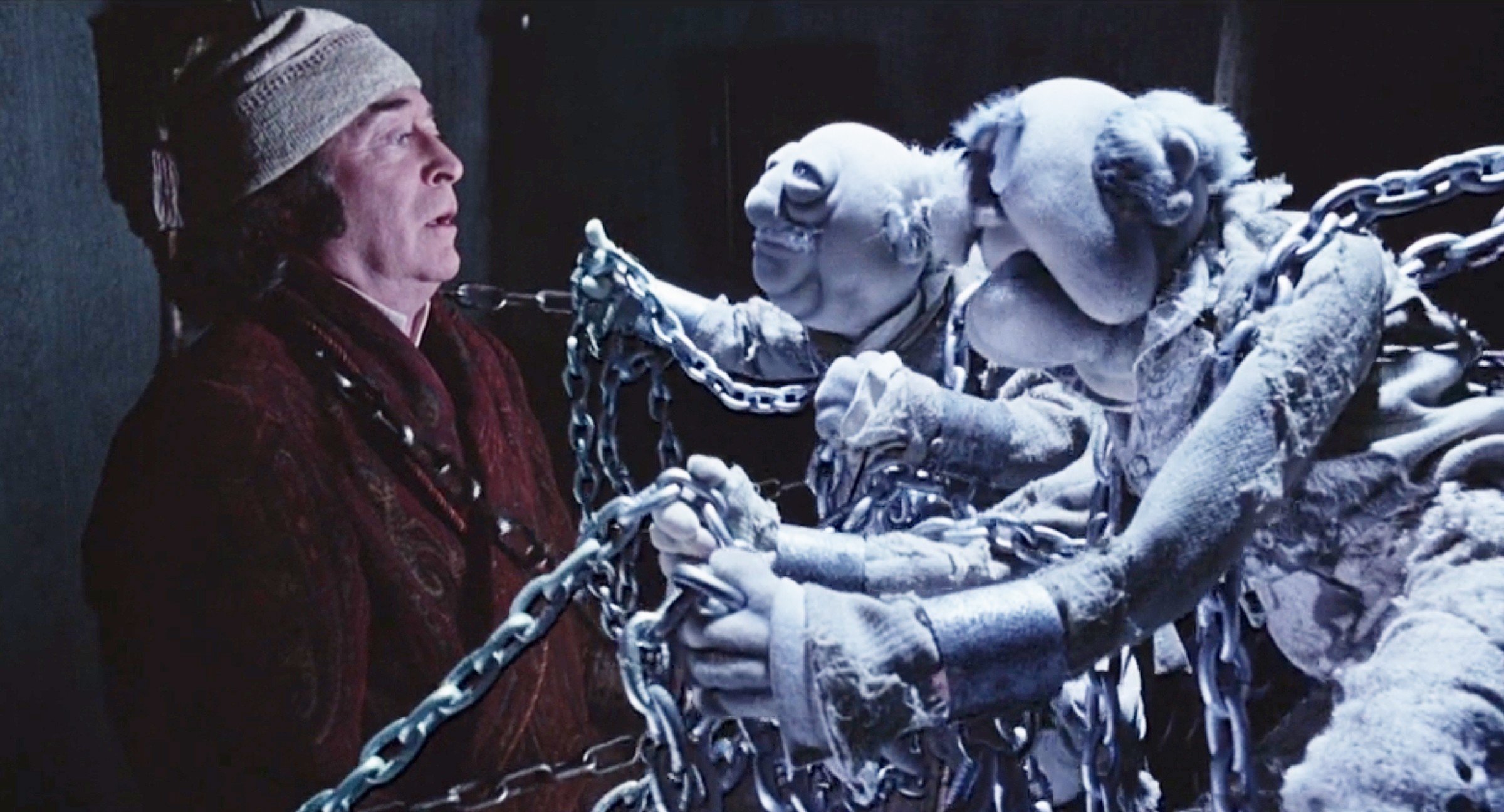

The Muppet Christmas Carol

I ended the year with the greatest Christmas movie of all time, The Muppet Christmas Carol, finally restored to the original version I remembered from my childhood VHS, with the crucial song that was bizarrely cut from the DVD for many years. This movie is somehow one of my favorite films of all time, even though it provokes my fear of hell and the pressure of some sort of works-repentance soteriology. Maybe that sounds like a silly reaction to Statler and Waldorf in ghostly chains, but it’s a real thing I struggle with, so it’s interesting that my affection for this is unimpaired. At any rate, the deeper pattern of the story rings true, and Caine gives an incredible performance. There’s no reason you couldn’t make any story, with every bit of its seriousness and sentiment, with muppets.

Auschwitz

In all honesty, I didn’t want to write a blog about visiting Auschwitz. It’s a serious place, and I’m not a very serious writer. What happened there is well known to us all, and I have nothing to add. Given this, it feels almost in poor taste. However, I decided I would write about my trip and the places I went, largely as a way of contextualizing and sharing my photos, and I’m not going to skip over perhaps the most important point I reached.

It was a surprisingly long journey by train from Prague, partly because the train idled for a long time near the border, partly because the town of Oświęcim (it’s proper Polish name) isn’t really on the way to anywhere. It’s out in the flat green countryside of southern Poland, and to get there I had to connect through Katowice and then go by local commuter rail. By the time I arrived it was already quite dark and cold; from the brightly-lit & recently rebuilt station, I walked about a mile along dim roads to the other side of town. There was nothing particularly historic or interesting along this way; just blank asphalt and miscellaneous businesses, a cheap restaurant here, a tire shop there. I’m not being quite fair to the town; I don’t think I really went to the best parts of it. That’s not why anyone goes there.

I stayed at the Catholic Centre for Dialogue and Prayer, built only a block from the first camp. It was as silent as the town around it, simple and spare. That night I watched Malick’s film A Hidden Life, about a conscientious objector from Austria during the war. It wasn’t directly related to the place I found myself, but it seemed apropos, felt correct.

In the morning, I toured the camps. For me, what surprised me most, although on reflection it shouldn’t have, was how normal everything felt. You arrive at what might be the single most horrifying place on earth, which is also an immense grave, and you come having been prepared for it by a lifetime of history and media. You expect great sorrow, and a sense of weighty reverence; you expect, perhaps, to cry. But mostly it just felt a little muted, a little hushed. It’s not a normal place, and yet in some sense it is. It was a sunny day, and everything felt very calm, and if you don’t have a direct connection to the place, it actually seems right to just be interested. It’s not really about you, after all.

Auschwitz I is in the town, and consists of normal brick buildings, with rows of trees and broad avenues. When you’ve been in Europe for two weeks, spending as much time as possible in the historical centers of cities, you almost don’t notice these buildings because they are so unremarkable, so dull. But that is itself the striking thing: these buildings are so modern, so much more recent than the average place you might stay in Europe, that they aren’t even worth noticing. That in itself is the greatest reminder of just how recent, how modern and contemporary this place is.

The interiors of the buildings create a double-effect, both emphasizing this sense of false normalcy – the flooring reminds me of the cheap tile still found in schools when I was growing up – but the rooms are filled with the detritus of lost lives. There are barracks, spare and uncomfortable, and yet not as bad as they would become at the second camp; there is a room, maybe fifty feet long, containing a pile of shoes that long and higher than my head; there is a whole room of crutches and prosthetic limbs, a reminder of the deliberate destruction of the disabled; there is a room of used canisters of gas; and there is an urn of human ashes, of who knows how many.

There was also a room which one is not allowed to photograph. This room has a pile as big as the pile of shoes – I would estimate perhaps fifteen feet deep, six feet high, and fifty feet long, though I have never been good at distances. This pile is made of women’s hair. It still retains some of its color – mostly brunette or grey, here and there a lock of blonde.