Les Miserables

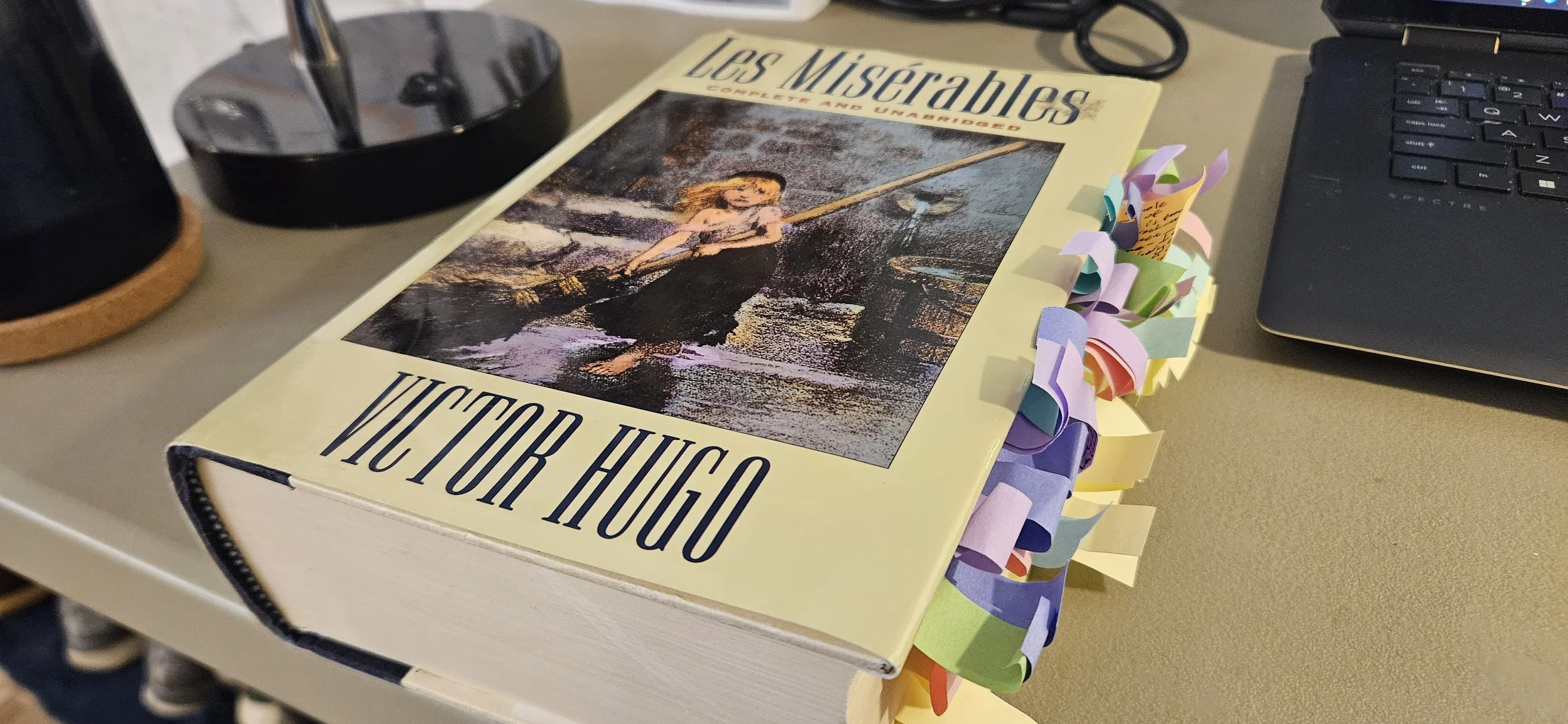

Many years ago I started reading Les Miserables, the novel with perhaps the greatest claim to be the Matter of France. I had grown up on the video recording of the 10th Anniversary Concert of the musical at Royal Albert Hall, which has always been far and away my favorite musical, so I was eager to finally dig into the book. I knew it was long; what I didn’t realize was that the entire first section was going to be an extremely detailed accounting of the everyday habits of an extremely charitable bishop. After seventy pages I paused, and didn’t pick up again until over a decade later (don’t worry, I started over from the beginning). This time I was surprised by just how easily all 1,222 pages went down—at no point did the novel drag, at no point did my interest flag, even when Hugo devotes an entire book to a description of the history and layout of the Parisian sewers so thorough that an engineer could probably use it to base a preliminary report on. Some of this is down to the excellent translation by Charles Wilbour, which I believe was the first translation into English, and which because of its contemporaneity with the novel carries with it the authenticity of the language of the day. The rest is down to Victor Hugo, who wrote what is probably going to go in my list as the third greatest novel I’ve read, after The Lord of the Rings and The Brothers Karamazov.

There is a whole world captured in all its complexity—not simply a perspective on the world, though Hugo voices his opinions with the confidence of a prophet, as he pulls together into one skein the whole complex tension of conflicting truths, and the full personhood, the imago Dei of every wretch on Earth. And it’s not simply a moment in time either—there are the judgements Hugo pronounces on history, whole worlds recalled in memory and nostalgia which had already ceased to exist when he set pen to paper, and then there is the world that shall be when tomorrow comes.

There were two aspects of the book which struck me most profoundly, one expected, one unexpected. The first is how much Hugo’s vivisection of the souls of Jean Valjean and Javert in their moments of crisis did not merely ring true, but actually mirror the precise patterns of guilty, anxious rumination that I remember from my own, much less dramatic, life. Several times Valjean goes through a dark night of the soul of exactly the sort I have lived my life fearing and trying to flee from. This is a story for people who, like Valjean, live in terror of what their conscience will demand of them, and for people like Javert, who are too afraid to ever accept unmerited grace. It is a book of truths which appear contradictory, but which are in fact inseparable.

The second aspect was how well Hugo’s magisterial pronouncements on history, humanity, progress, and the will of God put into words an apology for my own embryonic political theology. Hugo is both more clear-eyed about the darkest parts of humanity, and how deep those run, and more idealistic and hopeful than just about any other writer of fiction. In casting his gaze along the sweep of history’s rapid turning through the nineteenth century and into the future, he depicts what I can only call a non-Utopian eschatological progress. Hugo believes simultaneously in the importance of struggling to bring about a free world, to realize a millennial kingdom on earth that we each must help midwife, while also recognizing that our efforts will not bear fruit in our lives, that they will seem to fail completely, as the June rebellion did. The hope of fulfillment of this dream must rest firmly in God and eternity; and yet from God’s eternity, the inspiration breaking like the first fingers of dawn over the dim horizon should stir us to rise, even prematurely, and march East.

Quotes:

“So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation, which, in the face of civilization, artificially creates hells on earth, and complicates a destiny that is divine, with human fatality; so long as the three problems of the age—the degradation of man by poverty, the ruin of woman by starvation, and the dwarfing of childhood by physical and spiritual night—are not solved; so long as, in certain regions, social asphyxia shall be possible; in other words, and from a yet more extended point of view, so long as ignorance and misery remain on earth, books like this cannot be useless.”

“The scaffold, indeed, when it is prepared and set up, has the effect of a hallucination. We may be indifferent to the death penalty, and may not declare ourselves, yes or no, so long as we have not seen a guillotine with our own eyes. But when we see one, the shock is violent, and we are compelled to decide and take part, for or against. Some admire it, like Le Maistre; others execrate it, like Beccaria. The guillotine is the concretion of the law; it is called the Avenger; it is not neutral and does not permit you to remain neutral. He who sees it quakes with the most mysterious of tremblings. All social questions set up their points of interrogation about this axe. The scaffold is vision. The scaffold is not a mere frame, the scaffold is not a machine, the scaffold is not an inert piece of mechanism made of wood, of iron, and of ropes. It seems a sort of being which had some sombre origin of which we can have no idea ; one would say that this frame sees, that this machine understands, that this mechanism comprehends ; that this wood, this iron, and these ropes, have a will. In the fearful reverie into which its presence casts the soul, the awful apparition of the scaffold confounds itself with its horrid work. The scaffold becomes the accomplice of the executioner; it devours, it eats flesh, and it drinks blood. The scaffold is a sort of monster created by the judge and the workman, a spectre which seems to live with a kind of unspeakable life, drawn from all the death which it has wrought.”

“’Madame Magloire,’ replied the bishop, ‘you are mistaken. The beautiful is as useful as the useful.’ He added after a moment’s silence, ‘Perhaps more so.’”

“A saint who is addicted to abnegation is a dangerous neighbour; he is very likely to communicate to you by contagion an incurable poverty, an anchylosis of the articulations necessary to advancement, and, in fact, more renunciation than you would like; and men flee from this contagious virtue. Hence the isolation of Monseigneur Bienvenu. We live in a sad society. Succeed; that is the advice which falls, drop by drop, from the overhanging corruption.”

“What was more needed by this old man who divided the leisure hours of his life, where he had so little leisure, between gardening in the day time, and contemplation at night? Was not this narrow inclosure, with the sky for a background, enough to enable him to adore God in his most beautiful as well as in his most sublime works? Indeed, is not that all, and what more can be desired? A little garden to walk, and immensity to reflect upon. At his feet something to cultivate and gather; above his head something to study and meditate upon; a few flowers on the earth, and all the stars in the sky.”

“Here we must again ask those questions, which we have already proposed elsewhere: was some confused shadow of all this formed in his mind. Certainly, misfortune, we have said, draws out the intelligence; it is doubtful, however, if Jean Valjean was in a condition to discern all that we here point out. If these ideas occurred to him, he but caught a glimpse, he did not see; and the only effect was to throw him into an inexpressible and distressing confusion. Being just out of that misshapen and gloomy thing which is called the galleys, the bishop had hurt his soul, as a too vivid light would have hurt his eyes on coming out of the dark. The future life, the possible life that was offered to him thenceforth, all pure and radiant, filled him with trembling and anxiety. He no longer knew really where he was. Like an owl who should see the sun suddenly rise, the convict had been dazzled and blinded by virtue.

One thing was certain, nor did he himself doubt it, that he was no longer the same man, that all was changed in him, that it was no longer in his power to prevent the bishop from having talked to him and having touched him.

….

While he wept, the light grew brighter and brighter in his mind — an extraordinary light, a light at once transporting and terrible. His past life, his first offence, his long expiation, his brutal exterior, his hardened interior, his release made glad by so many schemes of vengeance, what had happened to him at the bishop's, his last action, this theft of forty sous from a child, a crime meaner and the more monstrous that it came after the bishop's pardon, all this returned and appeared to him, clearly, but in a light that he had never seen before. He beheld his life, and it seemed to him horrible; his soul, and it seemed to him frightful. There was, however, a softened light upon that life and upon that soul. It seemed to him that he was looking upon Satan by the light of Paradise.”

“They were of those dwarfish natures, which, if perchance heated by some sullen fire, easily become monstrous. The woman was at heart a brute; the man a blackguard: both in the highest degree capable of that hideous species of progress which can be made towards evil. There are souls which, crablike, crawl continually towards darkness, going back in life rather than advancing in it; using what experience they have to increase their deformity; growing worse without ceasing, and becoming steeped more and more thoroughly in an intensifying wickedness. Such souls were this man and this woman.”

“Some people are malicious from the mere necessity of talking. Their conversation, tattling in the drawing-room, gossip in the ante-chamber, is like those fireplaces that use up wood rapidly; they need a great deal of fuel; the fuel is their neighbour.”

“There are many of these virtues in low places; some day they will be on high. This life has a morrow.”

“Must he denounce himself? Must he be silent? He could see nothing distinctly. The vague forms of all the reasonings thrown out by his mind trembled, and were dissipated one after another in smoke. But this much he felt, that by whichever resolve he might abide, necessarily, and without possibility of escape, something of himself would surely die; that he was entering into a sepulchre on the right hand, as well as on the left; that he was suffering a death-agony, the death-agony of his happiness, or the death-agony of his virtue.

Alas! all his irresolutions were again upon him. He was no further advanced than when he began.

So struggled beneath its anguish this unhappy soul. Eighteen hundred years before this unfortunate man, the mysterious Being, in whom are aggregated all the sanctities and all the sufferings of humanity, He also, while the olive trees were shivering in the fierce breath of the Infinite, had long put away from his hand the fearful chalice that appeared before him, dripping with shadow and running over with darkness, in the star-filled depths.”

“Probity, sincerity, candour, conviction, the idea of duty, are things which, mistaken, may become hideous, but which, even though hideous, remain great; their majesty, peculiar to the human conscience, continues in all their horror; they are virtues with a single vice— error. The pitiless, sincere joy of a fanatic in an act of atrocity preserves an indescribably mournful radiance which inspires us with veneration. Without suspecting it, Javert, in his fear-inspiring happiness, was pitiable, like every ignorant man who wins a triumph. Nothing could be more painful and terrible than this face, which revealed what we may call all the evil of good.”

“This light of history is pitiless; it has this strange and divine quality that, all luminous as it is, and precisely because it is luminous, it often casts a shadow just where we saw a radiance; of the same man it makes two different phantoms, and the one attacks and punishes the other, and the darkness of the despot struggles with the splendour of the captain. Hence results a truer measure in the final judgment of the nations. Babylon violated lessens Alexander; Rome enslaved lessens Caesar; massacred Jerusalem lessens Titus. Tyranny follows the tyrant. It is woe to a man to leave behind him a shadow which has his form.”

“A certain amount of tempest always mingles with a battle. Quid obscurum, quid divinum. Each historian traces the particular lineament which pleases him in this hurly-burly. Whatever may be the combinations of the generals, the shock of armed masses has incalculable recoils in action, the two plans of the two leaders enter into each other, and are disarranged by each other. Such a point of the battle-field swallows up more combatants than such another, as the more or less spongy soil drinks up water thrown upon it faster or slower. You are obliged to pour out more soldiers there than you thought. An unforeseen expenditure. The line of battle waves and twists like a thread; streams of blood flow regardless of logic; the fronts of the armies undulate; regiments entering or retiring make capes and gulfs; all these shoals are continually swaying back and forth before each other; where infantry was, artillery comes; where artillery was, cavalry rushes up; battalions are smoke. There was something there; look for it; it is gone; the vistas are displaced; the sombre folds advance and recoil; a kind of sepulchral wind pushes forwards, crowds back, swells and disperses these tragic multitudes. What is a hand to hand fight? an oscillation. A rigid mathematical plan tells the story of a minute, and not a day. To paint a battle needs those mighty painters who have chaos in their touch. Rembrandt is better than Vandermeulen. Vandermeulen, exact at noon, lies at three o’clock. Geometry deceives; the hurricane alone is true. This is what gives Folard the right to contradict. Polybius. We must add that there is always a certain moment when the battle degenerates into a combat, particularises itself, scatters into innumerable details, which, to borrow the expression of Napoleon himself, ‘'belong rather to the biography of the regiments than to the history of the army.” The historian, in this case, evidently has the right of abridgment. He can only seize upon the principal outlines of the struggle, and it is given to no narrator, however conscientious he may be, to fix absolutely the form of this horrible cloud which is called a battle.”

“Was it possible that Napoleon should win this battle? We answer no. Why? Because of Wellington? Because of Blucher? No. Because of God.

For Bonaparte to be conqueror at Waterloo was not in the law of the nineteenth century. Another series of facts were preparing in which Napoleon had no place. The ill-will of events had long been announced.

It was time that this vast man should fall.

The excessive weight of this man in human destiny disturbed the equilibrium. This individual counted, of himself alone, more than the universe besides. These plethoras of all human vitality concentrated in a single head, the world mounting to the brain of one man, would be fatal to civilisation if they should endure. The moment had come for Incorruptible supreme equity to look to it. Probably the principles and elements upon which regular gravitations in the moral order as well as in the material depend, began to murmur. Reeking blood, overcrowded cemeteries, weeping mothers — these are formidable pleaders. When the earth is suffering from a surcharge, there are mysterious moanings from the deeps which the heavens hear.

Napoleon had been impeached before the Infinite, and his fall was decreed.

He vexed God.

Waterloo is not a battle; it is the change of front of the universe.”

“He felt in this a pre-ordination from on high, a volition of some one more than man, and he would lose himself in reverie. Good thoughts as well as bad have their abysses.”

“In the nineteenth century the religious idea is undergoing a crisis. We are unlearning certain things, and we do well, provided that while unlearning one thing we are learning another. No vacuum in the human heart! Certain forms are torn down, and it is well that they should be, but on condition that they are followed by reconstructions.”

“To be ultra is to go beyond. It is to attack the sceptre in the name of the throne, and the mitre in the name of the altar; it is to maltreat the thing you support; it is to kick in the traces; it is to cavil at the stake for undercooking heretics; it is to reproach the idol with a lack of idolatry; it is to insult by excess of respect; it is to find in the pope too little papistry, in the king too little royalty, and too much light in the night; it is to be dissatisfied with the albatross, with snow, with the swan, and the lily in the name of whiteness; it is to be the partisan of things of the point of becoming their enemy; it is to be so very pro, that you are con.”

“That evening left Marius in a profound agitation, with a sorrowful darkness in his soul. He was experiencing what perhaps the earth experiences at the moment when it is furrowed with the share that the grains of wheat may be sown; it feels the wound alone; the thrill of the germ and the joy of the fruit do not come until later.”

“M. Mabeuf’s political opinion was a passionate fondness for plants, and a still greater one for books. He had, like everybody else, his termination in ist, without which nobody could have lived in those times, but he was neither a royalist, nor a Bonapartist, nor a chartist, nor an Orleanist, nor an anarchist; he was an old-bookist.”

“There is under the social structure, this complex wonder of a mighty burrow, — of excavations of every kind. There is the religious mine, the philosophic mine, the political mine, the economic mine, the revolutionary mine. This pick with an idea, that pick with a figure, the other pick with a vengeance. They call and they answer from one catacomb to another. Utopias travel under ground in the passages. They branch out in every direction. They sometimes meet there and fraternize. Jean Jacques lends his pick to Diogenes, who lends him his lantern. Sometimes they fight. Calvin takes Socinius by the hair. But nothing checks or interrupts the tension of all these energies towards their object. The vast simultaneous activity, which goes to and fro, and up and down, and up again, in these dusky regions, and which slowly transforms the upper through the lower, and the outer through the inner; vast unknown swarming of workers. Society has hardly a suspicion of this work of undermining which, without touching its surface, changes its substance. So many subterranean degrees, so many differing labours, so many varying excavations. What comes from all this deep delving? The future.”

“There has been an attempt, an erroneous one, to make a special class of the bourgeoisie. The bourgeoisie is simply the contented portion of the people. The bourgeois is the man who has now time to sit down. A chair is not a caste.”

“All the problems which the socialists propounded, aside from the cosmogonic visions, dreams, and mysticism, may be reduced to two principal problems.

First problem:

To produce wealth.

Second problem:

To distribute it.

The first problem contains the question of labour.

The second contains the question of wages.

In the first problem the question is of the employment of force.

In the second of the distribution of enjoyment.

From the good employment of force results public power.

From the good distribution of enjoyment results individual happiness.

By good distribution, we must understand not equal distribution, but equitable distribution. The highest equality is equity.

From these two things combined, public power without, individual happiness within, results social prosperity.

Social prosperity means, man happy, the citizen free, the nation great.

England solves the first of these two problems. She creates wealth wonderfully; she distributes it badly. This solution, which is complete only on one side, leads her inevitably to these two extremes: monstrous opulence, monstrous misery. All the enjoyment to a few, all the privation to the rest, that is to say, to the people; privilege, exception, monopoly, feudality, springing from labour itself; a false and dangerous situation which founds public power upon private misery, which plants the grandeur of the state in the suffering of the individual. A grandeur ill constituted, in which all the material elements are combined, and into which no moral element enters.

Communism and agarian law think they have solved the second problem. They are mistaken. Their distribution kills production. Equal partition abolishes emulation. And consequently labour. It is a distribution made by the butcher, who kills what he divides. It is therefore impossible to stop at these professed solutions. To kill wealth is not to distribute it.

The two problems must be solved together to be well solved. The two solutions must be combined and form but one.

Solve the first only of the two problems, you will he Venice, you will be England. You will have like Venice an artificial power, or like England a material power; you will be the evil rich man, you will perish by violence, as Venice died, or by bankruptcy, as England will fall, and the world will let you die and fall, because the world lets everything fall and die which is nothing but selfishness, everything which does not represent a virtue or an idea for the human race.

It is of course understood that by these words, Venice, England, we designate not the people, but the social constructions; the oligarchies superimposed upon the nations, and not the nations themselves. The nations always have our respect and our sympathy. Venice, the people, will be reborn; England, the aristocracy, will fall, but England, the nation, is immortal. This said, we proceed.

Solve the two problems, encourage the rich, and protect the poor, suppress misery, put an end to the unjust speculation upon the weak by the strong, put a bridle upon the iniquitous jealousy of him who is on the road, against him who has reached his end, adjust mathematically and fraternally wages to labour, join gratuitous and obligatory instruction to the growth of childhood, and make science the basis of manhood, develop the intelligence while you occupy the arm, be at once a powerful people and a family of happy men, democratise property, not by abolishing it, but by universalising it, in such a way that every citizen without exception may be a proprietor, an easier thing than it is believed to be; in two words, learn to produce wealth and learn to distribute it, and you shall have material grandeur and moral grandeur combined; and you shall be worthy to call yourselves France.”

“Nothing is really small; whoever is open to the deep penetration of nature knows this. Although indeed no absolute satisfaction may be vouchsafed to philosophy, no more in circumscribing the cause than in limiting the effect, the contemplator falls into unfathomable ecstasies in view of all these decompositions of forces resulting in unity. All works for all.”

“The future belongs still more to the heart than to the mind. To love is the only thing which can occupy and fill up eternity. The infinite requires the inexhaustible.”

“Civil war? What does this mean? Is there any foreign war? Is not every war between men, war between brothers? War is modified only by its aim. There is neither foreign war, nor civil war; there is only unjust war and just war.”

“His supreme anguish was the loss of all certainty. He felt that he was uprooted. The code was now but a stump in his hand. He had to do with scruples of an unknown species. There was in him a revelation of feeling entirely distinct from the declarations of the law, his only standard hitherto. To retain his old virtue, that no longer sufficed. An entire order of unexpected facts arose and subjugated him. An entire new world appeared to his soul; favour accepted and returned, devotion, compassion, indulgence, acts of violence committed by pity upon austerity, respect of persons, no more final condemnation, no more damnation, the possibility of a tear in the eye of the law, a mysterious justice according to God going counter to justice according to men. He perceived in the darkness the fearful rising of an unknown moral sun; he was horrified and blinded by it. An owl compelled to an eagle’s gaze.

He said to himself that it was true then, that there were exceptions, that authority might be put out of countenance, that rule might stop short before a fact, that everything was not framed in the text of the code, that the unforeseen would be obeyed, that the virtue of a convict might spread a snare for the virtue of a functionary, that the monstrous might be divine, that destiny had such ambuscades as these, and he thought with despair that even he had not been proof against a surprise.

He was compelled to recognise the existence of kindness. This convict had been kind. And he himself, wonderful to tell, he had just been kind. Therefore he had become depraved.”